When I first sat down to learn how to use MassTransit, I found it difficult to just get a simple example that published a message onto the bus with another process that subscribed to messages of the same type working. Hopefully, this primer will get you on the bus quicker.

Setting Up Your Environment

The first thing you need is a message queuing framework. MassTransit supports MSMQ, RabbitMQ, and others, but I find that RabbitMQ is really the way to go. That’s especially true when using the publish/subscribe pattern. The reason for this is that RabbitMQ has a complete routing framework built-in and MassTransit will leverage this when persisting your subscriptions. When creating a cluster of RabbitMQ servers for availability, this routing information is replicated to all the nodes.

In this article, you’re going to run RabbitMQ on your local Windows development box. Both our publisher and subscriber will connect to the same RabbitMQ instance. In a future post, I’ll detail how to set up multiple RabbitMQ instances in a cluster.

Installing RabbitMQ

RabbitMQ requires the Erlang runtime, so that’s the first thing you need to download and install. Head over to Erlang.org’s download page and get the latest binary release for Windows (it’s likely you’ll want the 64-bit version). It’s a simple setup wizard, so you’ll have Erlang installed on your machine in short order.

Next, download the latest version of RabbitMQ for Windows. Again, it’s an easy setup wizard that you can quickly fly through. Just accept the defaults.

Enabling the RabbitMQ Web Management Interface

One RabbitMQ feature that I found extremely useful (but which isn’t enabled by default) is the web-based management interface. With this, you can see the exchanges and queues that are set up by MassTransit in RabbitMQ. To enable this, find the “RabbitMQ Command Prompt (sbin dir)” item that the RabbitMQ installer added to your Start menu and launch it. From the command line, run the following command:

> rabbitmq-plugins enable rabbitmq_management

It will confirm that the plugin and its dependencies have been enabled and instruct you to restart RabbitMQ. When installed on Windows, RabbitMQ runs as a Windows service. You can use the Services MMC snap-in to restart it or just run the following command:

> net service stop RabbitMQ ... > net service start RabbitMQ

Now go to http://localhost:15672/ to open the management console. Default credentials to login are guest/guest (you can change the credentials from the Admin tab).

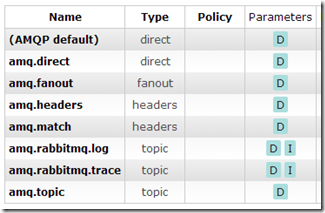

There’s not much to see yet, but we’ll set the stage. Go to the Exchanges tab. You’ll see the following default RabbitMQ exchanges:

An exchange is something you can send messages to. It cannot hold messages. It’s merely a set of routing instructions that tell RabbitMQ where to deliver the message. We’ll come back here in a little while.

Now click on the Queues tab. Nothing here yet. Queues can actually hold messages and are where applications can actually pick up messages.

So, to use a real world analogy, an Exchange is like the local Post Office, and a Queue is like your mailbox. The only thing that an Exchange can do that most traditional Post Offices don’t do is actually make multiple copies of a message to be delivered to multiple mailboxes.

Creating the Sample Applications

I used Visual Studio 2013 to create this sample, but it should work in 2012 as well. You can get the entire source from: https://github.com/dprothero/MtPubSubExample

Creating a Contract

I like to use the concept of a “contract” for my messages I want to put onto the service bus. This is an interface definition that both the publisher and subscriber have to agree upon. They don’t need to know anything about the implementation of this interface on either side. To keep the publisher and subscriber as loosely coupled as possible, I like to put my contracts in their own assembly so that this is the only shared dependency.

So, the first step is to create a new solution called MtPubSubExample and a new class library called “Contracts”. To the class library, add a single interface called “SomethingHappened.”

using System;

namespace Contracts

{

public interface SomethingHappened

{

string What { get; }

DateTime When { get; }

}

}

SomethingHappened will be the message interface we use for our sample message. Our publisher will create an instance of a class implementing SomethingHappened, set What and When properties, and publish it onto the service bus.

Our subscriber will then set up a subscription (aka Consumer) to listen for all messages of type SomethingHappened. MassTransit will call our Consumer class whenever a SomethingHappened message is received, and we can handle it as we wish, presumably inspecting the What and the When properties.

Shared Configuration Setup Code

When you’re writing a new project from scratch, you go through many permutations and refactor as you go. Initially, this example had the service bus setup code duplicated in both the publisher and subscriber projects. This is fine, particularly if you really aren’t in a position to share much code between the two sides (except the contracts of course). However, in my case, I preferred to use a common class which I’ll call “BusInitializer” to set up my instance to MassTransit and get it configured.

So, add another class library to the MtPubSubExample solution and name it “Configuration”. Before creating our class, it’s time to head to NuGet and pull in MassTransit. The quickest way to get everything you need is to find the MassTransit.RabbitMq package and install that. Doing so will install all of MassTransit and its dependencies.

You still need one more package. I found that MassTransit doesn’t work unless you install one of the logging integration packages that are designed for it. For me, I selected the Log4Net integration package (MassTransit.Log4Net).

Now, create a new class called “BusInitializer.”

using MassTransit;

using MassTransit.BusConfigurators;

using MassTransit.Log4NetIntegration.Logging;

using System;

namespace Configuration

{

public class BusInitializer

{

public static IServiceBus CreateBus(string queueName, Action<ServiceBusConfigurator> moreInitialization)

{

Log4NetLogger.Use();

var bus = ServiceBusFactory.New(x =>

{

x.UseRabbitMq();

x.ReceiveFrom("rabbitmq://localhost/MtPubSubExample_" + queueName);

moreInitialization(x);

});

return bus;

}

}

}

We’re creating a static method called “CreateBus,” which both our publisher and subscriber can use to set up an instance of a bus, using the Log4NetLogger, and connect to a local RabbitMQ instance. Because there may be additional custom setup that the publisher or subscriber may want to do, we allow passing in a lambda expression to perform the additional setup.

Creating the Publisher

We’ll make the publisher a very simple console application that just prompts the user for some text and then publishes that text as part of a SomethingHappened message. Add a new Console Application project called “TestPublisher” to the solution and add a new class called “SomethingHappenedMessage.” This will be our concrete implementation of the SomethingHappened interface. You’ll need to add a project reference to the Contracts (and add one to Configuration too, while you’re at it).

using Contracts;

using System;

namespace TestPublisher

{

class SomethingHappenedMessage : SomethingHappened

{

public string What { get; set; }

public DateTime When { get; set; }

}

}

Now, in the Main method of the Program.cs file in your Console Application, you can put in the code to set up the bus, prompt the user for text, and publish that text onto the bus. Real quick first, however, add a NuGet reference to the MassTransit package.

using Configuration;

using Contracts;

using System;

namespace TestPublisher

{

class Program

{

static void Main(string[] args)

{

var bus = BusInitializer.CreateBus("TestPublisher", x => { });

string text = "";

while (text != "quit")

{

Console.Write("Enter a message: ");

text = Console.ReadLine();

var message = new SomethingHappenedMessage() { What = text, When = DateTime.Now };

bus.Publish<SomethingHappened>(message, x => { x.SetDeliveryMode(MassTransit.DeliveryMode.Persistent); });

}

bus.Dispose();

}

}

}

Pretty simple, huh? We put the input capture and message publishing in a loop to make it easy to send multiple messages. Just put a catch for the string “quit” so we can exit the publisher when we’d like.

If you make TestPublisher the startup project of the solution and run it, right now you can publish messages all you like…. However, nobody is listening yet!

What’s Going on in RabbitMQ So Far?

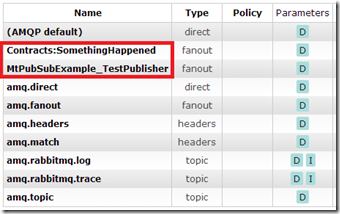

If you go back into the RabbitMQ web interface and jump over to the Exchanges tab, you’ll see we have a couple new arrivals.

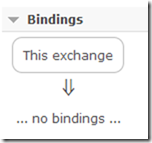

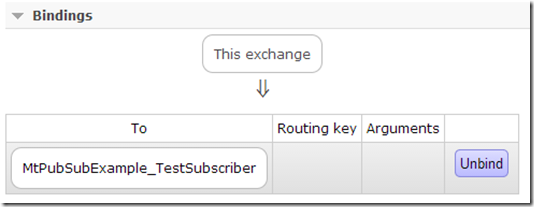

Contracts:SomethingHappened is a new exchange created for the SomethingHappened message type. When we published this message, MassTransit automatically created this exchange. Click on it and scroll down to the Bindings section, and you’ll see there are no bindings yet:

That’s because nobody has subscribed to SomethingHappened messages yet. They go to the exchange and then die because there’s no queue to route them to.

The MtPubSubExample_TestPublisher exchange (and corresponding queue on the Queues tab) were setup in our BusInitializer code. Our publisher isn’t listening for messages sent to it, so this isn’t really being used.

Creating the Subscriber

The final piece of the puzzle! Add another Console Application project to your solution and call it TestSubscriber. Again, add project references to Contracts and Configuration and then add the MassTransit NuGet package.

The first thing we need is a Consumer class to consume the SomethingHappened messages. Add a new class to the console app and call it “SomethingHappenedConsumer.”

using Contracts;

using MassTransit;

using System;

namespace TestSubscriber

{

class SomethingHappenedConsumer : Consumes<SomethingHappened>.Context

{

public void Consume(IConsumeContext<SomethingHappened> message)

{

Console.Write("TXT: " + message.Message.What);

Console.Write(" SENT: " + message.Message.When.ToString());

Console.Write(" PROCESSED: " + DateTime.Now.ToString());

Console.WriteLine(" (" + System.Threading.Thread.CurrentThread.ManagedThreadId.ToString() + ")");

}

}

}

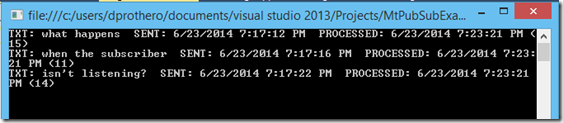

This consumer class implements a specific MassTransit interface whose Consume method will be called with the message context and SomethingHappened message each time a message is received. Here we are simply writing the message out to the console.

Finally, in the Main method of Program.cs, we can initialize the bus and, as part of the initialization, instruct MassTransit that we wish to subscribe to messages of type SomethingHappened.

using Configuration;

using MassTransit;

using System;

namespace TestSubscriber

{

class Program

{

static void Main(string[] args)

{

var bus = BusInitializer.CreateBus("TestSubscriber", x =>

{

x.Subscribe(subs =>

{

subs.Consumer<SomethingHappenedConsumer>().Permanent();

});

});

Console.ReadKey();

bus.Dispose();

}

}

}

Now right-click on the MtPubSubExample solution in the solution explorer and choose “Set Startup Projects….” From here, choose the Multiple startup projects option and set the Action for both TestPublisher and TestSubscriber to Start. Now when you run your solution, both the publisher and subscriber will run.

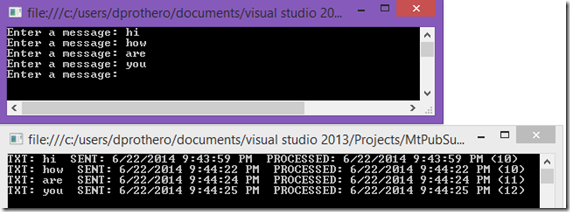

Type some messages into the publisher. You should see them show up immediately in the subscriber window!

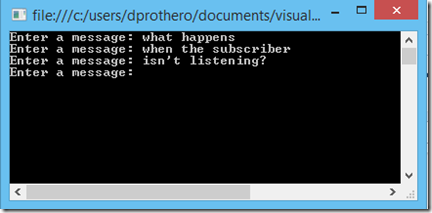

Now close just the Subscriber sample window and publish a few more messages in the Publisher window.

Go ahead and close the Publisher window for now. Let’s take a deeper look at where those three messages went.

What’s Going on in RabbitMQ Now?

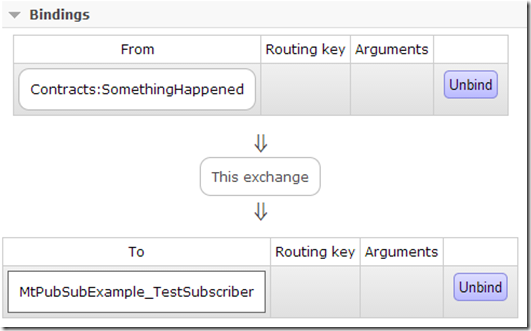

Go back into the RabbitMQ web interface and go back to the Exchanges tab. You’ll see a new exchange called MtPubSubExample_TestSubscriber, but first click on the Contracts:SomethingHappened exchange and scroll down to the Bindings section. You’ll see we now have a binding.

So, by creating a subscription from our TestSubscriber, MassTransit automatically set up this binding for us. Click on the MtPubSubExample_TestSubscriber here, and you’ll see you’re taken to the setup page for an exchange called MtPubSubExample_TestSubscriber. Scroll down to Bindings, and you’ll see we’re bound to a queue named the same as the exchange (in the binding diagrams, exchanges show up as rectangles with rounded corners, whereas queues have straight corners).

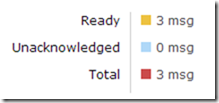

The web interface is great in how it shows the predecessor in addition to the successor in the path. Click the MtPubSubExample_TestSubscriber queue here, and you’ll be taken to the queue setup page for that queue. If you haven’t fired up the TestSubscriber app since we published those last three messages, you should see that there are three messages in the queue:

Fire up the TestSubscriber app, and you should see it process the three messages left in the queue.

Notice the timestamp from the message versus the timestamp of when the subscriber actually published the message. In this case, there was a 6-minute lag (the 6 minutes we were poking around in RabbitMQ before starting up the subscriber again).

Wrap Up

Hopefully, this post was helpful in getting you off the ground with MassTransit. There’s more to come. In upcoming posts, I’ll dig into how to put this together in the real world. First, your publisher and subscriber are likely to live on separate machines, so we’ll look at how to set up a RabbitMQ cluster to make that work. We’ll set up an ASP.NET application that publishes event messages and then a Windows Service that will subscribe to the messages and log them to a data store. Let me know if you have other examples you would like to see.

Until then…

Thanks, that was helpful in getting started.

This was really helpful when I was getting started with MT. Yours was the first article that really helped me fit it all together and make sense of it. Thank you!

Thanks so much for the comment, Sean. That’s what I was going for. Glad it was helpful.

Hi, thanks for great introduction to MT!

This is a great post to start using MassTransit with RabbitMQ, thanks for the detailed explanations and I hope we will see more posts about MassTransit in your blog (cause their documentation is not sufficient :))